Acropolis at Athens

Acropolis at Athens

Plan of the Acropolis

Parthenon

"Porch of the Maidens," the Erechtheum

photo courtesy of Professor Teresa M. Smith

Great Buildings Online - The Parthenon

http://buildings.greatbuildings.com/The_Parthenon.html

The Architecture of the Parthenon

https://members.tripod.com/caver352/architec.htm

The Parthenon Commentary

"The Parthenon...enjoys the reputation of being the most perfect Doric temple ever built. Even in antiquity, its architectural refinements were legendary, especially the subtle correspondence between the curvature of the stylobate, the batter, or taper, of the naos walls and the entasis of the columns."

—John Julius Norwich, ed. Great Architecture of The World. p63.

"The temple stands on the conventional three steps, below which the foundation platform originally created for its predecessor remained visible on the west, south and east sides of the building...The cella consisted of two rooms end to end with hexastyle prostyle porches...Inside the colonnades, towards the end, there stood the gold and ivory statue of Athena Parthenos, the work of Phidias, representing Athena fully armed with spear, helmet, aegis and, accompanied by a snake, and holding in her extended right arm a statue of victory. The ceiling was of wood, with painted and gilded decoration. Light was admitted, as normally in Greek temples, only through the doorway when the great doors were opened."

—Sir Banister Fletcher. A History of Architecture. p112.

Details

Dimensions of the temple at the top step are 30.9 m x 69.5 m (101 x 228 ft). The steps were 508 mm (20 in) high, "too high to use, so intermediate steps were provided at the centre of each of the short sides."

The eastern room was 29.8 m long by 19.2 m wide (98 ft x 63 ft), with internal Doric colonnades in two tier, structurally necessary to support the roof timbers.

On the exterior, the Doric columns measure 1.9 m (6ft 2in) in diameter and are 10.4 m (34ft 3in) high, approximately 5 1/2 times the diameter. The corner columns are slightly larger in diameter, with their spacing reduced to make it possible for the frieze to conform to the rule that it must terminate with a triglyph.

The stylobate has an upward curvature towards its centre of 60 mm (2 3/8 in) on the east and west ends, and of 110 mm (4 5/16 in) on the sides.

In the late sixth century the Parthenon was converted into a Christian church, and from about 1204, under the Frankish Dukes of Athens, it served as a Latin church, until in 1458 it was converted by the Turkish conquerors into a mosque.

—details taken from Sir Banister Fletcher. A History of Architecture. p112, 116.

Resources Sources on The Parthenon

Werner Blaser and Monica Stucky. Drawings of Great Buildings. Boston: Birkhauser

Verlag, 1983. ISBN 3-7643-1522-9. LC 83-15831. NA2706.U6D72 1983. plan and elevation

drawings, p23.

Roger H. Clark and Michael Pause. Precedents in Architecture. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1985. concentricity diagram, p203. reduction diagram, p213. — New 1996 edition, available at Amazon.com

Howard Davis. Slide from photographer's collection. PCD 2260.1012.0405. PCD 2260.1012.0405. PCD 2260.1012.0405.

Sir Banister Fletcher. A History of Architecture. London: The Butterworth Group, 1987. ISBN 0-408-01587-X. LC 86-31761. NA200.F63 1987. east elevation drawing, fig d, p114. discussion and details, p112, 116. — The classic text of architectural history. Expanded 1996 edition available at Amazon.com

Great Cities of the Ancient World : Athens & Ancient Greece. 1994. VHS-NTSC format video tape. ISBN 6303298591. — Video - Available at Amazon.com

G. E. Kidder Smith. Looking at Architecture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Publishers, 1990. ISBN 0-8109-3556-2. LC 90-30728. NA200.S57 1990. context photo, p18, close-up, 19.

Seton Lloyd, Hans Wolfgang Muller, Roland Martin. Ancient Architecture, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Crete, Greece. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1972. photo of south ambulatory, f394, p287.

John Julius Norwich, ed. Great Architecture of The World. New York: Random House, 1975. ISBN 0-394-49887-9. NA200.G76. discussion p63. Reprint edition: Da Capo Press, April 1991. ISBN 0-3068-0436-0. — An accessible, inspiring and informative overview of world architecture, with lots of full-color cutaway drawings, and clear explanations. Available at Amazon.com

Russell Sturgis. The Architecture Sourcebook. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1984. ISBN 0-442-20831-9. LC 84-7275. NA2840.S78. plan drawing of the Parthenon, p118.

Marvin Trachtenberg and Isabelle Hyman. Architecture, from Prehistory to Post-Modernism. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986. photo p90. — Available at Amazon.com

Doreen Yarwood. The Architecture of Europe. New York: Hastings House, 1974. ISBN 0-8038-0364-8. LC 73-11105. NA950.Y37. perspective drawing of acropolis, f29, p13. perspective drawing showing entablature, f23, p11. elevation drawing showing doric order, f13, p10. no image credit.

Great Buildings Model Kit : Great Buildings of the World. Julian Bicknell, Steve Chapman (Contributor). Clarkson Potter(June 1995). ISBN 0517883503. — A kit book with detailed pre-cut scale models of four famous buildings: Monticello, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Taj Mahal, and the Parthenon. available at Amazon.com

Kevin Matthews. The Great Buildings Collection on CD-ROM. Artifice, 2001. ISBN 0-9667098-4-5.— Available at Amazon.com

Source: http://buildings.greatbuildings.com/The_Parthenon.html

Columns of the Parthenon

How did the construction materials influence the structure of the columns?

Prior to the 5th century BC, Doric temple construction was mainly of wood. The great wealth of Periclean Athens, combined with Athens' population of skilled workers and slaves, and the desire for durable construction allowed the Parthenon to be built entirely of stone. The 20,000 tons of marble used to build the Parthenon came from quarries on Mount Pentelicon, about 10 miles from Athens. By the 5th century BC the Athenians had become skilled with simple machines: pulleys, levers, and inclined planes. Quarrymen and stonemasons used iron and wooden tools to hammer and wedge out blocks of marble. The size of each piece was cut according to the architect's specifications.

The heavy marble blocks were carefully brought down the mountain quarries on sleds that were controlled on ramps and roads that can still be seen today. They were then transported to Athens in ox-drawn carts. Larger pieces were carried on carts with wheels as large as 12 feet in diameter and pulled by as many as 30 teams of oxen. The trip to the Acropolis could have taken as long as two days. The marble was then carried up the slopes of the Acropolis on wagons pulled by mules.

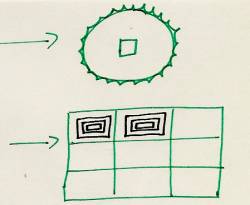

Blocks used for columns were cut into round drums with knobs that allowed them

to be lifted into place, probably by using rope pulleys over wooden structures.

The drums were divided into four circles each with a different finishing polish

that served to fit the drums precisely in place. The center was hollowed out

to allow the insertion of a wooden peg. No mortar was used in the construction

of the columns or elsewhere in the temple. With the drums in place, twenty,

deep fluted channels were cut around each column to add to the vertical line

of the column.

Source: http://www.mcdougallittell.com/whist/netact/U3/U3column.htm

The website of Professor Teresa M. Smith

http://iws.ccccd.edu/tsmith/greece.htm

|

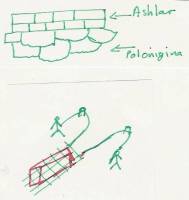

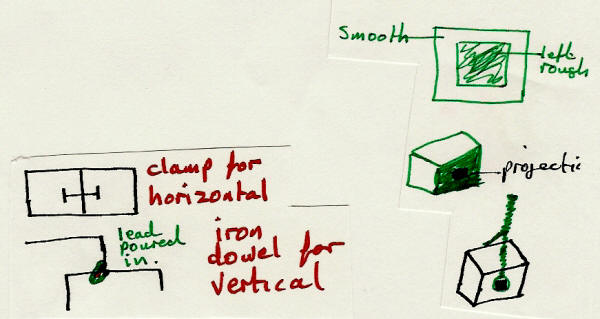

To support the temple a retaining wall was built. Poloniginal - shapes of stone meant no one point of weakness. No mortar was used. Then cut stone blocks were placed on top. Stones were hauled from the quarry on sleds or sometimes fastened on wheels or used teams of animals. Columns were not carved out of a single block of stone but were built with a series of drums and then held together with a wooden dowel through the center. Ceilings were often coffered (hollowed out) to

make them lighter. Blocks were quarried and finished at the site. Most blocks were smoothed and fitted together without any clamps, but sometimes metal lamps or dowels were necessary. Some stones were left with a projection to allow

pulleys to lift them into place. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|